When Approval Stops Meaning Control on the Factory Floor

Approval has long been treated as a proxy for control. If access is approved, it is assumed to be safe. If the request is logged and signed off, responsibility is considered transferred. This logic works reasonably well in office environments, where systems are stable, tasks are abstract, and deviations are rarely critical.

On the factory floor, this assumption does not hold. In OT environments, approval represents a decision made at a specific moment. What happens after that moment—during execution—is where many access-related failures begin to emerge.

Approval assumes stability that OT does not have

Approval-based access control is built on the expectation that the conditions present at approval time will remain valid when work is carried out. In IT environments, this expectation often holds. Approval and execution occur close together, systems behave predictably, and changes are usually reversible.

OT operations follow a different pattern. Maintenance windows shift. Equipment states evolve. Task scopes expand under operational pressure. Additional personnel may become involved after approval is granted. By the time access is exercised, the original conditions may no longer exist, even though the approval record remains valid.

The approval still exists. The context does not.

When approval drifts away from the work itself

Access in OT environments rarely involves a single individual performing a single action from start to finish. A supervisor may approve access, an external engineer may execute the task, and an operator may intervene during the process. Follow-up adjustments are often made under time pressure, using the same access path.

In these situations, approval no longer maps cleanly to responsibility. It confirms that a decision was made, but it does not reliably describe who performed which action, on which endpoint, and under what operational conditions. When incidents occur, organisations often have approval records, yet still struggle to explain what actually happened.

Approval exists, but control does not.

Time gaps turn approval into a snapshot

Approval is inherently static. OT operations are not.

In many environments, access is approved hours or days before it is used. During that gap, operational conditions can change significantly. What was acceptable at approval time may be unsafe at execution time. Yet access remains valid because approval mechanisms are not designed to reassess context once a decision has been made.

This creates a familiar illusion of governance. On paper, everything appears controlled. In practice, access gradually drifts away from the conditions under which it was authorised. The longer the delay between approval and execution, the weaker approval becomes as a safeguard.

Why approval records do not deliver accountability

Approval-based access control also assumes that documenting a decision is sufficient to establish accountability. In OT environments, this assumption repeatedly breaks down.

After an incident, approval logs can usually answer one question: who approved access. They struggle to answer the more important ones: who executed the action, whether it remained within scope, and whether conditions at execution time were still acceptable.

This gap is not the result of poor logging or weak process discipline. It is structural. Approval systems are designed to validate intent. OT incidents emerge from execution.

Why adding more approval rarely helps

When approval-based controls show weaknesses, organisations often respond by adding more layers: additional reviewers, longer checklists, and more formal sign-off processes. These measures increase friction without restoring control.

More approvals do not resolve the underlying mismatch between static decisions and dynamic operations. Instead, they slow down work and encourage informal workarounds, including shared credentials and standing access that bypass the approval process altogether. The outcome is often reduced visibility, not improved control.

At this point, the limitations of approval as a primary control mechanism become difficult to ignore.

What approval can and cannot do in OT

Approval is not irrelevant in OT environments, but it is frequently overestimated. It can express intent, support governance processes, and satisfy certain audit requirements. What it cannot do is enforce correct execution in a changing operational context.

On the factory floor, effective access control must remain connected to how work is actually performed. This means acknowledging conditions that approval alone cannot address:

- access may be exercised long after it is approved

- multiple actors may act under a single approval

- execution conditions may diverge from the original scope

- responsibility may fragment as work progresses

As long as approval is treated as the end of control rather than one input into it, these gaps will persist.

A necessary reset in how approval is used

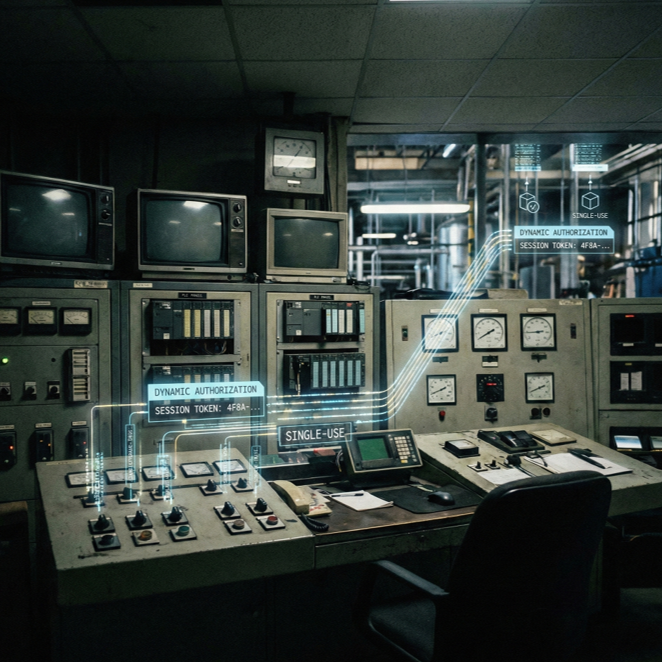

In OT environments, approval should not be treated as a switch that permanently enables access. It should function as one element within a broader access control structure—one that remains bound to the task, the endpoint, and the conditions under which the work is actually performed.

Until access control reflects how work unfolds in operational environments, approval will continue to offer reassurance without protection. And in OT, reassurance alone is not a substitute for control.

--------------------

swIDch will continue its quest to innovate and pioneer next-generation authentication solutions. To stay up-to-date with the latest trends sign up to our newsletter and check out our latest solutions.

At a large industrial site, a contractor needed temporary access to a controller to complete routine maintenance. The

At a large manufacturing plant in Northern Europe, a routine maintenance task nearly became a shutdown. An external

For many OT organisations, Passwordless still feels abstract. The concept is attractive — fewer credentials, fewer

Looking to stay up-to-date with our latest news?